Photo: Giulia McGauran

Tones And I

news

Tones And I Talks Her New Album 'Welcome To The Madhouse,' Opens Up About The Menace Of Online Bullying

Australian indie-EDM sensation Tones And I just released her debut album and most personal work to date, 'Welcome to the Madhouse.' But she won’t be going on social media to enjoy the attention—and here, she courageously opens up about the online bullying

Tones And I used to perform in a completely vulnerable state—alone, afterhours on the streets of Byron Bay, surrounded by soused barcrawlers. "On the street, I put myself in positions where, in the middle of the night, drunk and disorderly people are everywhere," the singer/songwriter born Toni Watson tells GRAMMY.com over Zoom. "And still, no one has yelled or said profanities like they do online."

How could this be possible? It's called deindividuation—when people join up with mobs, they do things they wouldn't do alone. This goes triple for social media, where you can pick any name you want and replace your face with a pickup truck avatar. Under cover of anonymity, these types have tormented Tones And I to the point of sending death threats, prompting fear for her family.

"I just feel like it's getting to the point where a whole bunch of artists are going to start talking about it," she says. "It's a good thing to bring up. We have a voice."

Tones And I uses her voice in two ways—her literal one calls attention to Instagram vultures and her musical one sings about her deepest fears, joys and anxieties. Those feelings permeate her new album, Welcome To The Madhouse, which was released July 16. Its songs, like "Fly Away," "Fall Apart" and "Dark Waters"—which she wrote at various points in her life—paint a complicated portrait.

With all her challenges in the music business, does the good still outweigh the bad for Tones And I? Find her answer below—along with ruminations on her busking past, losing a loved one and overcoming hatred to find peace.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//V91GRYjlR2I' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Nice to meet you. Where are you located?

I'm back in Byron Bay, where I used to busk.

What was in your repertoire?

"Dance Monkey," actually. I played that for almost a year before I released it. I was never going to release it. That and four other originals. The rest was a bit of Disclosure, a lot of Chet Faker.

Usually, when you busk, you go for something a 65-year-old in flip-flops might know. I respect the more obscure choices.

Yeah, also, I busked with synthesizers and loop pedals, so it wasn't your typical [setup].

One time, the whole power in the town went out and none of the buskers were connected to the powerpoints in the stores. I was the only busker that kept going. Everyone flooded into the streets and had to get out of the buildings because the power was out in town. The whole road was full with a thousand people and no one could see anything. The girls were holding their phone lights over my keyboard to keep playing. Everyone was singing "Hey Ya!" in the street. It was sick.

What was it like to watch your breakout hit grow from a busking environment?

Yeah, it was insane. Crazy.

I used to do this cover of "Forever Young" [by Alphaville] and every time I played it, people would get up and start dancing. I wanted a song that was my own that you could dance to, so originally, I just wrote that song for my friends. I didn't even want to release music, to be honest. I didn't think there was anything good from releasing music because I didn't know any better. I just wanted to busk.

Tell me about the palette of colors you used for Welcome To The Madhouse—the inspirations behind its making.

That's really hard. I've always said that every song I write is inspired by some mood or even another song, but this album was definitely not a mood for me.

The fact that it's turned into a nicely wrapped box with a bonnet because I called it Welcome To The Madhouse and the music is depressed, happy then sad—I made it like that so it would all fit into that album nicely, but the reason is it was also written over the last two years.

I've got songs from when I first got to Byron Bay, before I started busking, when I started busking, when I went on my first world tour and when [my friend] passed away. It was from such different times that there's no way this album was going to be one mood, or one time in my life.

When I wrote "Fly Away," the lyrics were so genuinely honest to how I was feeling. It could be quite sad, but I wanted to have a moment in that song where it felt really happy and very up-and-about and made you feel good. But, if you want to listen to it properly, you can listen to the slower version where I took that production out. It can show you that there's a really sad side to the song. It became my good friend's funeral song when he passed away.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//R0vu5QfsD5E' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

My condolences. Can I ask what happened?

So, we'd all just gone away together because we had this tiny little moment in Australia where there was no COVID. We got back and we were at the beach all day for one of our good friend's birthdays. That morning, I got a call at 6 a.m. He drove into a pole and flung through the windshield and hit the road and died.

I'm OK with talking about it because people like to pretend online that he did it to himself. They don't know what's going on, so I guess maybe if I just say it once, people will understand that it was nothing like that. He was an amazing, happy person and he got into a car accident.

That's absolutely awful. Tell me about him in life, though. What kind of a person was he? What did he mean to you?

Well, he was probably the one in the group that brought everyone together—the girls and the boys. He was the loudest one, but in the nicest way. He wasn't rude or obnoxious. He was fair to everyone. He never got involved in anything if anyone was having any arguments. He wasn't just the closest one to the younger ones, like us, but also the parents. There are a lot of different places around his world that are really significantly hurt by this. He's got such a good heart.

Anyway, I met him probably 10 to 12 years ago, growing up. He's dealt with a lot in that time. His dad passed away. His brother's got cerebral palsy, so at the moment, I'm housing his brother. I've got his brother in a place where he can live on his own because he told me before he died that was one thing he wanted to do—to get his brother out of his grandparents' house because they were getting too old to deal with it.

It's a weird balance between expressing yourself and making a commercial product. How did your response to this translate into the tunes?

Well, there was a period where I originally tried to write songs about the person that he was, but that was too hard for me. So, when I wrote "Fall Apart," I wrote about the fact that we can't really deal with it yet in the way I wanted to. I tried the way I wanted to talk about him and who he was with the world in the music, which is the way a lot of musicians would talk.

I tried to talk about him, but I couldn't. So, I wrote "Fall Apart," which is really about how much we miss him and we're thinking about him.

People online were saying his death was his own fault? What's wrong with them?

There's a lot of stuff online, especially when I release anything. Online sucks. It brings people to a place where they don't know what happened, so they just create a story. Everyone does. If you don't give people enough information, they're going to create a story.

The story was that he was sad. [Beneath] the photos we would put up remembering him, they would say things like "Look how sad he looks!" and all that. I [even had to] convince his mom that he was a happy person. I'm trying to tell his mom, who wants more clarity, that he was a really happy person. I had to lock down that he would never do that.

Do you deal with other types of online bullying outside of your friend?

The fact that you ask makes me feel really good, because I thought I was famously known for it. It's really bad. I'm off social media, which sucks. Being a new artist, you're excited. It's so hard. You want to be authentic. Sometimes, it does affect you a little bit when there's whole, huge videos on their YouTube accounts about you. They also make them about other artists, too.

I need to realize, at the end of the day, it feels like it's always me because I am me. But there are other people, too. There are so many people who are going through it. It's just that I am me. I'm upset about things that happen to me. But when I see someone say something about another artist, I'm automatically really frustrated toward that person because it's absolutely freaking horrible. It's not about me for a second.

Tones And I. Photo: Giulia McGauran

Speaking stranger-to-stranger, I don't think you "need" to do anything in response. This is a cruel environment. The onus is on online bullies to cease their behavior, not on you.

Thanks for saying that. It makes me feel better. I just don't want my family—my nana and pa—to see that. They're so proud of me when I see them and I would never share that stuff with them. And now, they see it and it's so sad. I don't want my papa to see that stuff online and my nana. It gets pretty outrageous. I keep my head down. I talk about what I care about, but I don't go on comments and stuff. If I looked for it, I'd probably not come out of the house.

The reason I decided to become a busker and not a YouTube artist is that I wanted to play live. I wanted to play on the street. On the street, I put myself in positions where, in the middle of the night, drunk and disorderly people are everywhere, and still, no one has yelled or said profanities like they do online.

If you decide to stop on the street, that's your call. You can walk on, just like you can swipe away. But no one yells out s*** before they leave in front of everyone because they're held accountable, right in the moment, for what they do. Online stuff is really tricky. Everyone is like a warrior.

I hope the good outweighs the bad for you in this business.

Yeah, it does. It does. I just feel like it's getting to the point where a whole bunch of artists are going to start talking about it. It's a good thing to bring up. We have a voice. Whether I'm the biggest artist in the world or the smallest, I think it's really important to mention it. I always tell my friends that kindness stops bullies.

Give me a line on Welcome To The Madhouse that carries special weight for you.

I would say the bridge of "Dark Waters": "I don't see the world I got / But I keep rolling on / 'Cause I am never happy with enough / Until I'm drowning from it all." That song I wrote at the point where "Dance Monkey” had just gone No. 1, so I was at the peak of my "Holy s***!"-ness. My first billboard in Times Square. I had just gone to the States and played sold-out shows. I had just started a Europe tour as well.

And then, I got to a point where—I don't know why, but I was so sad. Maybe because my dreams as a busker, I had been pulled from that really quickly. Like, "Cool, we had fun. Let's do this." I didn't know why I was so sad. I kept trying to do more and more things, like "This will make me happy," but then it wasn't. I think I needed to be home and be grounded and see my friends. I got picked up and flung around the world. But that's where that line comes from.

Do you have a message for your trolls and haters?

I love you! Hopefully, we can meet in person one day. I just announced a U.S. tour, so if you want to come meet me in person, that's fine. Tickets are open for everyone. We don't discriminate at Tones And I shows. Also, I hope you listen to the album if you haven't. It isn't all the same, so I guess there's a song for—I'm not going to say everyone—the majority of you if you listen and pay attention. I had fun making it and I hope you guys enjoy it.

That's very magnanimous of you. No implied threat in there.

[Knowing laugh.] No, no. No, no.

San Holo Gets Personal With New Indie Rock EDM Album 'BB U Ok?'

Photo: Drewby Perez

interview

Ladies And Gentlemen, Glass Animals Are Floating In Space

For Glass Animals, breaking through with their last album during the pandemic was an isolating experience. They brought those feelings to the fore with 'I Love You So F—ing Much,' where the Englishmen embrace a sort of majestic, celestial loneliness.

Remember the atmospheric river of 2024? Glass Animals' Dave Bayley thought he'd drown in it. He'd holed up in a cheap Airbnb to write his band's latest album, I Love You So F—ing Much — and soon realized why it was so cheap.

"When I got there, I realized why. It was one of those stilt houses, hanging off the edge of a cliff," Bayley tells GRAMMY.com. "There was s— flying down and trees coming out of the ground, flying down the mountain. I was like, I'm dead. This is it. This is the end."

Late at night, observing the bedlam of the natural world, Bayley didn't feel planted on terra firma at all; he felt as if he was floating in space. Which turned out to be the impetus for the English indie-psych-poppers' latest statement — space being a metaphor for disconnection and unmooring. (The album arrived July 19 via Republic; Bayley remains the sole producer.)

"I think I had a lot of imposter syndrome, and felt very disconnected from reality as well," Bayley says of the Covid era — which unfortunately dovetailed with the breakout success of their last album, Dreamland. But by some strange alchemy, Glass Animals spun that feeling into emotional warmth.

As you absorb songs like "Creatures in Heaven," "A Tear in Space (Airlock)" and "Lost in the Ocean," read on for an interview with Bailey about how this celestial, lonesome, yet oddly swaddling and comforting album came to be.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

How would you describe the four-year gap between Dreamland and I Love You So F—ing Much?

Like lifetimes, honestly. And at the same time, it sort of feels like yesterday as well.

It's very, very confusing — because we finished Dreamland, and then Covid hit. We were about to release it, and then we postponed, and postponed, and realized the pandemic is not going away. We promised people the album; we needed to release it to, like, survive. So, we released it thinking it would probably tank. And it did something absolutely amazing, unexpected.

Most people, when something like that happens, get to be out and experience it, and see it happening in the real world — playing live shows, and they feel part of it, and it's part of them. Whereas I was trapped in my bedroom in my underpants watching it all happen through social media and email updates.

You needed to make it to survive? Say more about that.

I mean, that was our livelihood. Somehow, this has become a profession — I have to pinch myself when I say that, it's the best thing ever.

But you can't just not release music. You have to keep writing and releasing music to maintain it as a profession. We were four years out from the record before that, at that point.

Odd question: if a music career was inaccessible to you, what would be your professional destiny, as it were?

I was trying to be a doctor before all of this happened. I was four years deep into medical school, actually. Then, a series of strange and terrible things happened in my life that made me like, I want to take a break from med school.

I was using music as a therapy, almost, to get over some of the things that had happened. I was making music to feel better, really, and connected somehow. Someone, somewhere, maybe, put it on SoundCloud.

**What was the thematic seed of I Love You So F—ing Much?**

I guess that sense of detachment was a big thing — because it not only went for the duration of the pandemic, but even after the pandemic, we were touring. And because there was no insurance for people touring against Covid, we still had to isolate and bubble within ourselves. It was going to extend us another year and a half, just being in this metal tube.

It was like, the biggest shows we ever had — they were amazing. We'd walk on stage, and for an hour and a half, be slammed in the face with emotion and energy. And then we'd walk offstage back to the bus, and we couldn't interact and be part of what was happening afterwards.

It just made us all feel even more surreal — it felt like a dream.

Talk about the sound you wanted to capture.

This one, I wanted to sound a specific way; I knew the equipment to get. I got about six synths and 20 pedals that fit the sound — a couple of guitars and a drum kit that fit the sound — and I just went for it. You could turn anywhere, and the sound would fit into the context of the record.

**If you think of Glass Animals' discography as stops on a journey via train, which stop is I Love You So F—ing Much?**

We've reached this retro-futuristic stuff, and I think it's definitely a progression from the last album.

I definitely set my own kind of '90s, '80s production — and now there's a bit of a vaporwave thing going on, but it was still pretty analog and nostalgic. It seems to be almost like the train went backwards.

Then, on the songwriting side, I was trying to really make sure the core of the sounds had [integrity]; they could basically be played with guitar and voice alone. I wanted the chords to tell the story of the song as well; we'd kind of done that in the past, but I'd never really focused on it like I did this time.

I wanted the chords to keep evolving through each section of the song — just twist the atmosphere of the song in each section.

Give me a line on I Love You So F—ing Much that you feel sums up what we're talking about.

"Show Pony" is the first song; everyone creates this idea of love, and what love should be, based on what they've seen and experienced growing up. Seeing their family, seeing their friends — you're walking down the street, and you see a couple arguing, and you form these [impressions of] love.

"Show Pony" is kind of the blueprint; it gives context for the rest of it. And then, the line that comes right after it: "What the hell is happening? What is this?" I like that as the real beginning of the record, after the table of contents — the first song.

Where do you think Glass Animals will go from here?

It's a good question, because I don't really think I'm there yet. I have a few ideas — but to be honest with you, I never end up going with any of the first ideas that I have.

Before this iteration of the album, I wrote a whole other space album that just felt really cold and hollow and empty — like a vacuum. It wasn't cool; it didn't have enough emotion, and it didn't feel soulful enough. I just binned it, and sacked off; it's in the trash.

It wasn't until I stumbled on this concept of juxtaposing these kinds of small, intimate moments with the size of space, that I put two and two together — and worked out how I could do a space album without it being f—ing s—.

Explore More Alternative & Indie Music

Chelsea Cutler & Jeremy Zucker On Why 'Brent iii' Is "A Nice Way To Close The Page" On Their Musical Partnership

The Linda Lindas Talk 'No Obligation,' Cats & Working With Weird Al

Why BoyWithUke Is Already Retiring His Alter Ego

Get To Know Declan McKenna, The British Rocker Shaking Up The Indie Scene

Radiohead Performs "15 Step" At The 2009 GRAMMYs

Photo: Ebru Yildiz

interview

X's Mark The Spot: How Cigarettes After Sex Turn Difficult Memories Into Dreamy Nostalgia

"We’re all in the same boat," Greg Gonzalez says of the band’s new album, ‘X’s.' The frontman speaks with GRAMMY.com about how channeling Madonna and Marvin Gaye helped him turn his memories of a relationship into sublime dream pop.

When Greg Gonzalez sat down to start writing the next Cigarettes After Sex album, the dream pop frontman relied equally on memories of heartbreak and the ballads of the Material Girl. "‘90s Madonna was a big influence on this record," he tells GRAMMY.com with a soft smile.

Though the end result won’t be mistaken for anything off of Ray of Light, that timeless, almost mystic cloud of emotionally resonant pop carries a distinct familiarity on Cigarettes After Sex's new album, X’s.

Cigarettes After Sex has championed that sweet and sour dreaminess since their 2017 debut. Two years after that self-titled record earned rave reviews and was certified gold, the El Paso, Texas-based outfit reached even deeper for Cry. And while those records cataloged Gonzalez's heartbreaks and intimacies in sensual detail, Gonzalez knew he could reach deeper on the band’s third LP: "These songs are just exactly as memory happened."

Arriving July 12, X’s fuses Cigarettes After Sex's dream pop strengths with ‘90s pop warmth and ‘70s dance floor glow. Always one to bring listeners into the moment, Gonzalez imbues the record with a lyrical specificity that gives the taste of pink lemonade and the tension of a deteriorating relationship equal weight. On X’s, the listener can feel the immediate joy and lingering pain in equal measure.

"This is specific to me and what I'm going through, but then I go out and talk to people on tour, and they’re like, 'Oh, yeah, I went through the exact same thing,'" Gonzalez says.

Leading up to the release of X’s, Gonzalez spoke with GRAMMY.com about the appeal of ‘90s Madonna, finding a way to dance through tears, and his potential future in film scoring.

Tell me about the production process for this record. You've always been able to build nostalgic landscapes, but this record feels smoother than before. Were there any new touchpoints you were working with?

That was the thing: trying to make the grooves tighter. It was coming from more of a ‘70s Marvin Gaye kind of place, trying to make it groove like a ‘70s dance floor.

Which is an especially interesting place to be writing from when dealing with that line between love and lust.

Yeah. The stuff we've done before was really based on the late ‘50s, early ‘60s slow dance music. But it was always supposed to be dance music; I always wanted Cigarettes to be music you could dance to, even if it was a slow dance.

When I think of pop music and I think of songs that really feel powerful, they usually make you want to groove in some way. I love a lot of music that doesn't do that: ambient music or classical or some jazz. But there's so much power to music that makes you want to move. And I found throughout the years that I could just never get enough of the music that makes you want to dance. So I thought, Okay, the music that I make should be really emotional. It should feel like music you could actually cry to, but in the end it should make you want to also move in that way.

It’s the physical necessity of the music, some forward motion to match the emotional journey. I’d imagine that is related in some sense to the fact that you’re writing in a somewhat autobiographical way. Is that a way of not getting stuck in the stories, in the feelings?

I'm writing it for myself. Of course, I can't help but picture the audience in some way. But it's never like I'm writing it for them.

There is an audience that I can visualize that would like the music. [Laughs]. There have been times where we’re recording and I close my eyes to visualize an arena or a stadium to picture the music in that setting. It’s a nice feeling. And that's just based on the music that I love that I thought had similarities.

Is there any particular music that you love that fills that feeling?

There's so much music that I was obsessed with, but with Cigarettes I narrowed it down. Since I was a kid, I did every kind of style I could do. I was in power pop bands, new wave, electro, metal, really experimental bands.

But when I finally sat down and said, "Let me make an identity for Cigarettes and make it special," I had to think about what my favorite music was and what music affected me the deepest. And it was stuff like "Blue Light" by Mazzy Star or "Harvest Moon" by Neil Young or "I Love How You Love Me" by the Paris Sisters. And I kind of put all that together and that became the sound of Cigarettes. And now I do that every time I make a record: I'll make a playlist of what I want it to feel like. I mentioned Marvin Gaye. I feel like ‘90s Madonna was a big influence on this record.

Madonna in the ‘90s? No one could touch that era. I don't know when the last time you listened to that music was, but…

No, I grew up with Madonna and I used to watch the "Like A Prayer" video on repeat. It blew me away. But then I came back and I got into the ‘90s stuff, like "Take A Bow" and that record Something To Remember. It's all of the slower tunes. And that was a big influence, especially songs like "Rain."

You clearly have a diverse musical appetite, but you’ve also highlighted people with such identifiable voices — something that I think is true for Cigarettes as well. Your vocals are so front and center in the identity of the project.

That's great. The singer pretty much makes the song for me, whatever I’m listening to. The entire spirit comes down to the vocals. I'll hear a song like "Take A Bow" and be like, This feels so special. What if I made something that felt like this? If I told someone this [record] was based on Marvin Gaye and ‘90s Madonna, I don’t know if they would think it really sounded like that. It's more just trying to capture the spirit of what those records feel like.

That's what's cool about it too: You can remember those songs that were filling the air back in the ‘90s and what those feelings were, what you were up to, and draw a line between that and whatever's happening now that I wrote about.

You don’t seem like the type of person to avoid negative feelings when you come up against them in that process either. The songs feel like you just embrace it, even if it's really painful.

I've always felt that's the best way for me to go through things, to face it head on. It's supposed to be painful. You have all these really great moments with somebody and all these great memories, and then when it ends, honestly, that's the way it goes, right? That's the trade off.

Yeah, but not everybody goes through a breakup and then makes an album about it. Isn’t that like returning to the scene of the crime? How does it feel to deal with it in that way?

That's funny. The thing was, I was writing a lot of this stuff while I was still in a relationship. It took so long to finish it.

Finish the album or finish the relationship? [Laughs.]

Actually both. But yeah, the record is mostly about that one relationship, but there are little diversions with some of the songs. A lot of the key images and songs are based on that romance and little memories that I took from it.

I like that I have all those moments kind of set in stone. It’s hard to listen to this record too because I'll just really see these moments, all these memories, and it can be a bit much to flash back to all that stuff and see it so vividly. But I love that I have it. Those memories meant so much and I’m glad that they're collected and displayed in this way.

And you were able to collect them when it was happening as opposed to having some time between, which could warp those memories. Writing and recording when you’re as raw as possible makes sense, so what you capture is really honest.

That's why I like to write these songs that are as honest as possible or as autobiographical as possible, with a lot of details. If I'm writing a song and someone heard it, they would know it was about them just based on all the imagery that's in that song. It's like a little letter to them. It could be like a secret little letter to someone.

That makes me think of "Holding You, Holding Me," which is so lovely and feels as immediate as anything you’ve done.

It was the pandemic, and then the other girlfriend I had at that time, we were living in downtown L.A. and just wanted to get out of the house and stay somewhere nicer for a while. And we went to this AirBnb that was in Beverly Hills with this beautiful backyard. The song was meant to be kind of Fleetwood Mac-ish, like "Gypsy" or "Sara", that nice ‘70s country pop feel.

Over the years I’ve noticed you frequently use taste as a sensory link in your songs, which really creates an evocative moment — I’m thinking about references to candy bars and lemonade on this album. What is it about that sense that sticks out to you?

If I'm going back to memory, then that's just what really happened. We went to the store to go buy wine and candy because that was the vibe that night. "Let’s watch movies and get red wine and some candy bars." And it was just a big memory that we walked outside and it started raining. I think too, what's nice about using objects is that it gives you so much mood in a song. You can tell what the feeling is of that moment when you put those things together.

And it can have an almost universal understanding. People will understand what it means to have a "candy bar night."

That's the craziest thing. It's almost like you're trained to write universally, meaning generically. Like, "Oh, this is a song that everyone can like and the lyrics can be really simple." But I’ve found that the songs that are really detailed and were more personal stories, a song like "K." from Cigarettes After Sex, those are the songs that everyone really loves, the ones that take up being really specific.

I suppose that's pop's way of being a doorway. When you're talking about your personal experiences, somebody is going to enter into it and feel like you're singing about theirs.

You realize that we're all in the same boat. This is specific to me and what I'm going through, but then I go out and talk to people on tour, and they’re like, "Oh, yeah, I went through the exact same thing." I feel very lucky that most people I talk to that love [our] music are always saying that. It’s so special.

It makes me trust my instincts. That's the hard thing when you're writing. You're wondering, Is this too much to disclose? Is this too much information? [Laughs.] That instinct is really important to know, to trust it. That's the tough one. That's what's also therapeutic about it too. You want to share things that feel really personal because then you can process them. You can really start to unpack what those moments meant and what they can mean going forward. It gives me more confidence when I hear that kind of stuff from people.

What then is it like when you sing it for a crowd? You’re performing, but you can’t fully separate the emotion that inspired that song.

That's tough because, ideally, if I did my job well enough writing the song, then it should be hard to sing live — especially if I really see those moments when I'm singing it. It could bring me to tears, honestly, because it should feel that intense. And it's even worse if I look in the crowd and someone's crying. I can't even look at them. And that happens very often. If I started crying, my voice will stop.

That brings a real cinematic feeling to your music too, which makes me think you’d be good at scoring a film. Is that something you’d tackle?

I'm definitely obsessed with film and have been since I was a kid. The idea that I keep saying — and I almost feel like I'm going to jinx it because I keep saying it too much — is that I really want to direct and write something. And I've written some ideas down for screenplays and things. It seems like it's hard to transition from musician to filmmaker and really make it stick. But that would be something I want to do in the next 10 years. I'm giving myself 10 years. [Laughs.]

Latest News & Exclusive Videos

How Major Lazer's 'Guns Don't Kill People…Lazers Do' Brought Dancehall To The Global Dance Floor

YOASOBI Performs "Idol" | Global Spin

'Wicked' Composer Stephen Schwartz Details His Journey Down The Yellow Brick Road

GRAMMY Museum Expands GRAMMY Camp To New York & Miami For Summer 2025

Living Legends: Brooks & Dunn On How 'Reboot II' Is A Continuation Of "Winging It From Day One"

Photo: Mike Formanski

interview

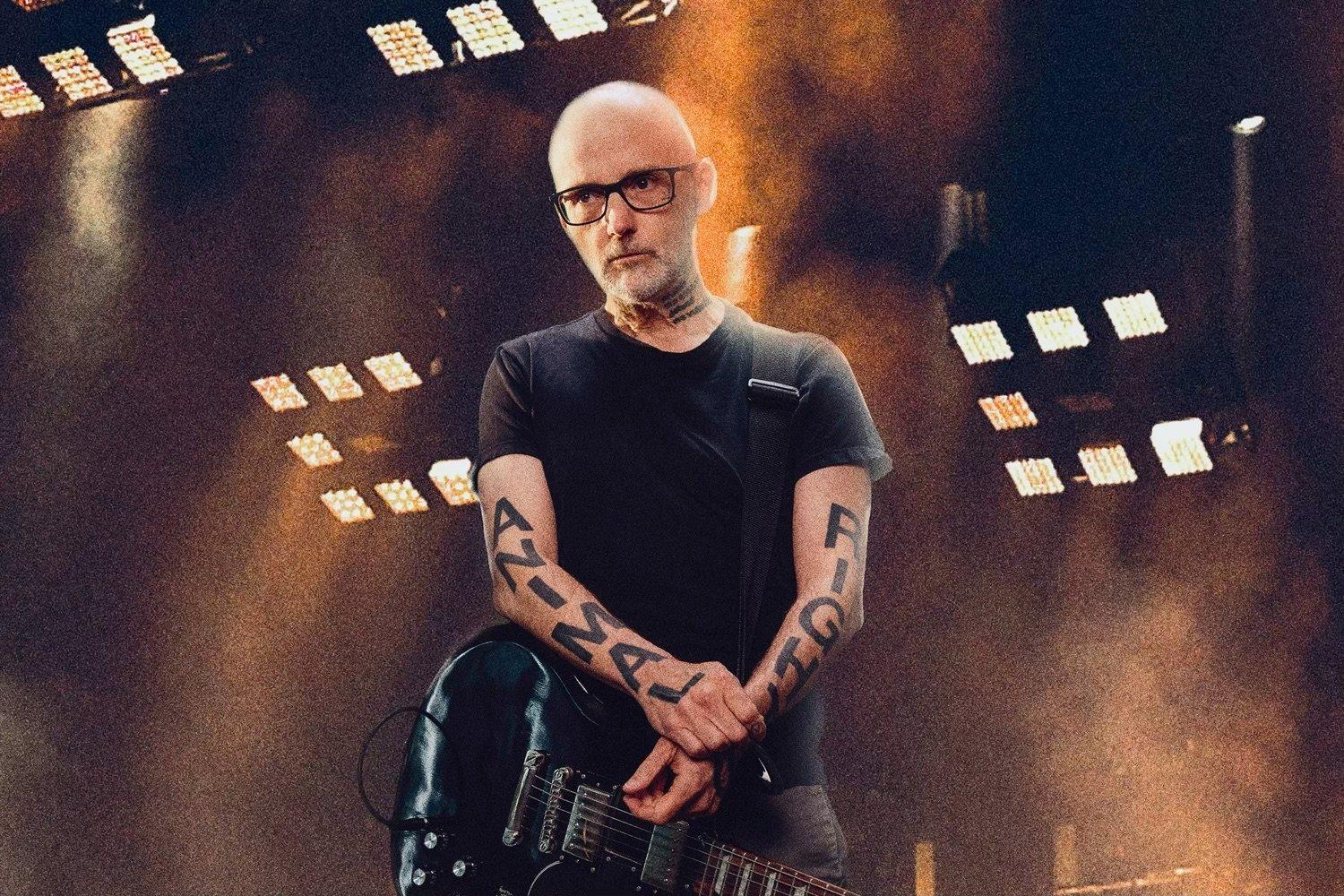

"Let Yourself Be Idiosyncratic": Moby Talks New Album 'Always Centered At Night' & 25 Years Of 'Play'

"We're not writing for a pop audience, we don't need to dumb it down," Moby says of creating his new record. In an interview, the multiple-GRAMMY nominee reflects on his latest album and how it contrasts with his legendary release from 1999.

Moby’s past and present are converging in a serendipitous way. The multiple-GRAMMY nominee is celebrating the 25th anniversary of his seminal work, Play, the best-selling electronic dance music album of all time, and the release of his latest album, always centered at night.

Where Play was a solitary creation experience for Moby, always centered at night is wholly collaborative. Recognizable names on the album are Lady Blackbird on the blues-drenched "dark days" and serpentwithfeet on the emotive "on air." But always centered at night’s features are mainly lesser-known artists, such as the late Benjamin Zephaniah on the liquid jungle sounds of "where is your pride?" and Choklate on the slow grooves of "sweet moon."

Moby’s music proves to have staying power: His early ‘90s dance hits "Go" and "Next is the E" still rip up dancefloors; the songs on Play are met with instant emotional reactions from millennials who heard them growing up. Moby is even experiencing a resurgence of sorts with Gen Z. In 2023, Australian drum ‘n’ bass DJ/producer Luude and UK vocalist Issey Cross reimagined Moby’s classic "Porcelain" into "Oh My." Earlier this year, Moby released "You and Me" with Italian DJ/producer Anfisa Letyago.

Music is just one of Moby’s many creative ventures. He wrote and directed Punk Rock Vegan Movie as well as writing and starring in his homemade documentary, Moby Doc. The two films are produced by his production company, Little Walnut, which also makes music videos, shorts and the podcast "Moby Pod." Moby and co-host Lindsay Hicks have an eclectic array of guests, from actor Joe Manganiello to Ed Begley, Jr., Steve-O and Hunter Biden. The podcast interviews have led to "some of the most meaningful interpersonal experiences," Moby tells GRAMMY.com.

A upcoming episode of "Moby Pod" dedicated to Play was taped live over two evenings at Los Angeles’ Masonic Lodge at Hollywood Forever Cemetery. The episode focuses on Moby recounting his singular experiences around the unexpected success of that album — particularly considering the abject failure of his previous album, Animal Rights. The narrative was broken up by acoustic performances of songs from Play, as well as material from Always Centered at Night (which arrives June 14) with special guest Lady Blackbird. Prior to the taping, Moby spoke to GRAMMY.com about both albums.

'Always centered at night' started as a label imprint then became the title of your latest album. How did that happen?

I realized pretty quickly that I just wanted to make music and not necessarily worry about being a label boss. Why make more busy work for myself?

The first few songs were this pandemic process of going to SoundCloud, Spotify, YouTube and asking people for recommendations to find voices that I wasn’t familiar with, and then figuring out how to get in touch with them. The vast majority of the time, they would take the music I sent them and write something phenomenal.

That's the most interesting part of working with singers you've never met: You don't know what you're going to get. My only guidance was: Let yourself be creative, let yourself be idiosyncratic, let the lyrics be poetic. We're not writing for a pop audience, we don't need to dumb it down. Although, apparently Lady Blackbird is one of Taylor Swift's favorite singers.

Guiding the collaborators away from pop music is an unusual directive, although perhaps not for you?

What is both sad and interesting is pop has come to dominate the musical landscape to such an extent that it seems a lot of musicians don't know they're allowed to do anything else. Some younger people have grown up with nothing but pop music. Danaé Wellington, who sings "Wild Flame," her first pass of lyrics were pop. I went back to her and said, "Please be yourself, be poetic." And she said, "Well, that’s interesting because I’m the poet laureate of Manchester." So getting her to disregard pop lyrics and write something much more personal and idiosyncratic was actually easy and really special.

You certainly weren’t going in the pop direction when making 'Play,' but it ended up being an extremely popular album. Did you have a feeling it was going to blow up the way it did?

I have a funny story. I had a date in January 1999 in New York. We went out drinking and I had just gotten back the mastered version of Play. We're back at my apartment, and before our date became "grown up," we listened to the record from start to finish. She actually liked it. And I thought, Huh, that's interesting. I didn't think anyone was going to like this record.

You didn’t feel anything different during the making of 'Play?'

I knew to the core of my being that Play was going to be a complete, abject failure. There was no doubt in my mind whatsoever. It was going to be my last record and it was going to fail. That was the time of people going into studios and spending half a million dollars. It was Backstreet Boys and Limp Bizkit and NSYNC; big major label records that were flawlessly produced. Play was made literally in my bedroom.

I slept under the stairs like Harry Potter in my loft on Mott Street. I had one bedroom and that's where I made the record on the cheapest of cheap equipment held up literally on milk crates. Two of the songs were recorded to cassette, that's how cheap the record was. It was this weird record made by a has-been, a footnote from the early rave days. There was no world where I thought it was going to be even slightly successful. Daniel Miller from Mute said — and I remember this very clearly — "I think this record might sell over 50,000 copies." And I said, "That’s kind of you to say but let's admit that this is going to be a failure. Thank you for releasing my last record."

Was your approach in making 'Play' different from other albums?

The record I had made before Play, Animal Rights, was this weird, noisy metal punk industrial record that almost everybody hated. I remember this moment so vividly: I was playing Glastonbury in 1998 and it was one of those miserable Glastonbury years. When it's good, it's paradise; it's really special. But the first time I played, it was disgusting, truly. A foot and a half of mud everywhere, incessant rain and cold. I was telling my manager that I wanted to make another punk rock metal record. And he said the most gentle thing, "I know you enjoy making punk rock and metal. People really enjoy when you make electronic music."

The way he said it, he wasn't saying, "You would help your career by making electronic music." He simply said, "People enjoy it." If I had been my manager, I would have said, "You're a f—ing idiot. Everyone hated that record. What sort of mental illness and masochism is compelling you to do it again?" Like Freud said, the definition of mental illness is doing the same thing and expecting different results. But his response was very emotional and gentle and sweet, and that got through to me. I had this moment where I realized, I can make music that potentially people will enjoy that will make them happy. Why not pursue that?

That was what made me not spend my time in ‘98 making an album inspired by Sepultura and Pantera and instead make something more melodic and electronic.

After years of swearing off touring, what’s making you hit stages this summer?

I love playing live music. If you asked me to come over and play Neil Young songs in your backyard, I would say yes happily, in a second. But going on tour, the hotels and airports and everything, I really dislike it.

My manager tricked me. He found strategically the only way to get me to go on tour was to give the money to animal rights charities. My philanthropic Achilles heel. The only thing that would get me to go on tour. It's a brief tour of Europe, pretty big venues, which is interesting for an old guy, but when the tour ends, I will have less money than when the tour begins.

Your DJ sets are great fun. Would you consider doing DJ dates locally?

Every now and then I’ll do something. But there’s two problems. As I've become very old and very sober, I go to sleep at 9 p.m. This young guy I was helping who was newly sober, he's a DJ. He was doing a DJ set in L.A. and he said, "You should come down. There's this cool underground scene." I said, "Great! What time are you playing?" And he said "I’m going on at 1 a.m." By that point I've been asleep for almost five hours.

I got invited to a dinner party recently that started at 8 p.m. and I was like, "What are you on? Cocaine in Ibiza? You're having dinner at 8 p.m. What craziness is that? That’s when you're putting on your soft clothes and watching a '30 Rock' rerun before bed. That's not going out time." And the other thing is, unfortunately, like a lot of middle aged or elderly musicians, I have a little bit of tinnitus so I have to be very cautious around loud music.

Are you going to write a third memoir at any point?

Only when I figure out something to write. It's definitely not going to be anecdotes about sobriety because my anecdotes are: woke up at 5 a.m., had a smoothie, read The New York Times, lamented the fact that people are voting for Trump, went for a hike, worked on music, played with Bagel the dog, worked on music some more went to sleep, good night. It would be so repetitive and boring.

It has to be something about lived experience and wisdom. But I don't know if I've necessarily gotten to the point where I have good enough lived experience and wisdom to share with anyone. Maybe if I get to that point, I'll probably be wrong, but nonetheless, that would warrant maybe writing another book.

Machinedrum's New Album '3FOR82' Taps Into The Spirit Of His Younger Years

Photo: Bethany Vargas

interview

The Marías Plunge Into The Depths On 'Submarine': How The Band Found Courage In Collective Pain

Following a major breakup, group therapy and finding solace in film, the Marías are back with a new album of ethereal pop. "It is my perspective on heartbreak, which can be interpreted in so many different ways," says singer/songwriter María Zardoya.

The Marías had undergone a seismic change by the time they started working on Submarine, their second full-length album. Lead singer and songwriter María Zardoya and drummer and producer Josh Conway had ended their eight-year relationship, uprooting their lives and creative partnership in the process.

Instead of being subsumed by the breakup's emotional waters, the L.A.-based pop band took a six month hiatus. They traveled, tended to their loved ones, and considered the next steps for their careers.

Luckily for their large, devoted audience, Zardoya and Conway decided that their breakup wasn’t an obstacle for the Marías to keep going. "Even though you lose yourself in every heartbreak, I think that is an opportunity to gain even more," Zardoya tells GRAMMY.com.

What followed was a fruitful period at their Los Angeles studio, where Zardoya, Conway, keyboardist Edward James, and guitarist Jesse Perlman reassessed their dynamics. They spent long days working on new songs, pushing through with the help of band and individual therapy. The end result is Submarine, a record that tells a story of loneliness, grief, and transformation.

Submarine is a vibrant listening experience, and reflective of the Marías' love of film and well-curated aesthetics. The album is full of expansive arrangements, ranging from dream pop to rock and jazz. Water-like sounds, R&B harmonies, and soft electronic textures add to Zardoya’s ethereal vocals which, complimented by shimmery guitars and subtle percussion, create a contrasting narrative of desolation and romance.

The group’s musical union, and their distinctive sound, is palpable through Submarine. Tight-knit danceable songs, cheeky vocals, and Zardoya’s immaculate style — which seeps through lyrics about drama, paranoia, and even the claustrophobic feeling behind modern technology — make for a strong release, where love and hope are still within reach.

Ahead of their world tour, which kicks off in Mexico on June 11, and in celebration of Submarine, the Marías spoke with GRAMMY.com about overcoming the band’s potential dissolution, taking inspiration from arthouse cinema, and the emotional process of creating their third album.

Looking at your docuseries for 'Submarine,' something María said caught my attention. "There were a few moments after ‘Cinema’ that I thought the band was over." Can you elaborate on that?

María Zardoya: There was a point where I did think that the band was over. I think we were all in a tumultuous place. I didn't know if I still wanted to make music, and I didn't know if The Marías would continue. But thankfully, it did.

We went to therapy as a band; Josh and I went to therapy together; and we all started doing our [own] therapy. Through all of that work that we did, we realized that the music is so important. We have so much to say, and what we have to say is important. Let's continue.

In the end, that period only made us stronger. Today our relationship with each other, and my relationship with Josh and the guys individually are stronger than ever. So I'm glad that we went through what we did.

Can each of you, individually, tell me why the band is important to you?

Josh Conway: Music has been important to me my entire life. That's something that I kind of realized over the last couple of years; music is more important to me than anything else. I'll do whatever it takes to continue making music and making music with people that I love, especially. It's special to be doing this with all my best friends.

Edward James: I've always wanted to be in a band. I love the concept of a group of people who are one for all and all for one, and who get to experience everything together. It's a unique interpersonal relationship dynamic that you don't get really with anyone else in your life. So apart from the existential pursuit of music that we're all drawn to, the camaraderie is so important, because of how difficult the dynamic is to maintain and to continue. I think doing it with the band sort of translates to every other sort of relationship you can have in your life.

Jesse Perlman: Whether if we took one year off, or five years off, we would still, at some point, get back together and be like, "Okay, we're ready." I think we're so close, and we miss touring so much. This whole rollout and recording process that we did in the last year has just been so open — and I think we're just so ready to take this on the road.

Zardoya: It's important to express myself, and to get out the feelings that are inside. That's why music is so important to me, and this band is so important to me. I've gotten a lot of DMs and letters in the mail from fans saying that our music has helped them through different periods in their lives. That they feel seen, and represented — with them being Latin and me being Latin — and how inspired they are. So music is important for me individually, but it's also important for me to keep doing this for the people who get something out of our music.

Jesse, you mentioned missing touring. What is everyone's favorite part of touring? A lot of musicians have detailed how touring can be grueling and financially unviable.

Perlman: We're coming up on almost eight years of being in this band, and I feel like we've done it all. We've gone around the country so many times now, and that was special. But now we're at a level where we finally have a whole crew and we can play these bigger, beautiful theaters.

We can make a cool, eclectic setlist with a mix of all the songs [from Submarine, Cinema and EPs Superclean Vol. I and II] — and that's my favorite part, putting together a fun set. Surprising the fans with interludes and jams and a big production with cool lights and stuff. That’s so fun for me.

James: My favorite part of touring is just that feeling of nervousness before a show. Then sort of going over the hilltop as soon as we play the first notes of the first song. Then riding that feeling during and after the show.

Conway: All of the trouble of getting to and from the venue, carrying gear, and the off days in a random city — all of that can be pretty grueling and taxing. But when you can play these songs, in front of fans that love you, and love your music and sing along. You can see people experiencing joy. It makes it all worth it, 99 percent of the time.

Going back to the process of making 'Submarine,' María, you mentioned a transition between thinking the band was over to making music again. Can you tell us more about that moment?

Zardoya: I think we took the intensity of Josh [Conway] and me transitioning from a romantic relationship to a platonic relationship and put it into the music. [We] also used it to work on ourselves and grow individually. I'm grateful for everything that we've been through, the intense moments and the hard moments because we just put it into music.

How did you start and arrive at the theme of the album? From having an "aha moment" to completing the project?

Zardoya: The aha moment came when the album title came into my head. I shared it with the guys and they were super into it. That's when the album’s world started to be built. When we started hearing how it could all come together, that’s when Submarine— the title and the concept — was born. I saw so much symbolism in using water to represent this going inward, this introspective journey that we were all on. And then using these underwater sounds in the tracks.

Conway: There was also a moment when we had been working on the album for a couple of months. We had gotten to a good place after writing, and then María and I listened to the first six songs that are on the album now. That was the first time where María and I were able to conceptualize what it's gonna sound like when you listen to the whole album. We were dancing in the studio and that was just a really exciting moment. We both knew we just heard the beginning of the album and we loved it.

You did a great track-by-track breakdown of your 2021 album, 'Cinema.' Can you talk about the tracks in 'Submarine?'

Zardoya: The opening track, "Ride," is almost like an introduction to Submarine. Where Cinema started with these beautiful string arrangements, we kind of wanted the first track of Submarine to be a little bit more hard-hitting and in your face. Almost like it's slapping you into this world.

Perlman: The intro to Cinema was dramatic. Then when you listen to "Ride" opening Submarine, it's more fun and light-hearted.

Conway: Then "Hamptons." María and I were cycling through old beats, and that one caught our attention. We just started writing to it. We pretty much had the whole thing written on the first day. It was a lot of fun.

Zardoya: I think thematically I wrote these lyrics after visiting the Hamptons. I wanted to hate the Hamptons because it's like this bougie place in New York, but I honestly loved it. It was beautiful. The nature was so pretty.

What about "Echo" and "Real Life"?

Zardoya: "Echo" is about being pulled into two different directions and living in that ambivalence, which makes you feel paralyzed. This was probably one of the hardest songs to write on Submarine — both thematically and then also piecing it together. We had a part written and it wasn't quite doing it. Then finally, one afternoon the chorus came out of nowhere. And then I think we were like "Okay, here we go. We've got the song."

"Real Life," lyrically, is about the culture that we have with our phones, and everything being virtual. It’s about wanting to have that one-on-one human connection in real life. Songwriting-wise, it came out of a jam that we were all doing together in the Dominican Republic. We were there for a show. We started jamming and it all — the melody, lyrics, and everything — came out of nowhere.

James: It was pretty much written in 30 minutes. It was crazy fast.

Perlman: Whenever we play it, it's perfect every time. It's always the first one we soundcheck with. It's one of my favorites on the album.

In a YouTube video, you said that 'Submarine' is not necessarily about your heartbreak. Can you expand on that?

Zardoya: Words in songs live subconsciously, within me. These songs could be about us, they could be about something that happened 10 years ago, they don't have to be about anything in particular. They are subconscious thoughts that come up to create a song. It is my perspective on heartbreak, which can be interpreted in so many different ways.

Have any films or music helped inspire or complement the aesthetic of 'Submarine?'

Zardoya: I've always been inspired by visuals when it comes to what we do and how it merges with the music. Film was like my first love. One of the movies that inspired this album, 'Three Colors: Blue' by Krzysztof Kieślowskii, from the 'Three Colours' trilogy. Aside from the color blue, and how we've moved from red to blue in this album, in that movie, the main character loses her family at the beginning and she has to figure herself out and go on this introspective journey to find herself.

That's kind of how I felt with this album. In the beginning, I found myself in this place of solitude and loneliness. Then throughout the album, just like Julie in the movie, I started to find myself and started to find courage in the pain that I had been feeling.

Other movies that I rewatched during the making of this album were 'Lost In Translation' and 'Her.' 'Lost In Translation' is also about solitude, and I found that perspective inspiring the visuals and the record as well. Then on 'Her', technology and loneliness kind of go hand in hand. All of these relationships that we have with technology and with our phones were kind of interspersed throughout the album.

Later I discovered that these two films were created in response to the end of a relationship [between film director Sofia Coppola and filmmaker Spike Jonze]. So I loved that as well because you create this art in response to something real and something tangible.

In making 'Submarine,' did you learn something or find a silver lining?

Conway: You don't have to be in a romantic relationship to love someone.

Zardoya: Even though you lose yourself in every heartbreak and every loss, I think that you have an opportunity to gain even more.

Conway: When the album ends, there is a glimmer of hope. In my mind, it feels like that you'll be getting out of the submarine pretty soon.

Wallows Talk New Album 'Model,' "Entering Uncharted Territory" With World Tour & That Unexpected Sabrina Carpenter Cover